|

|

Kashima Antlers have established themselves as the most successful team in J.League history. Their well-stocked trophy cabinet includes eight league title trophies and 11 major cup trophies, as well as a host of minor titles like the Suruga Cup, Xerox Cup, Stage titles, and so on. Their championship run last season, followed by a Club World Cup debut in which they took a full-strength Real Madrid to extra time, reiterated their well-deserved reputation as Japan’s most successful football team.

The “Golden Herd of Ibaraki” are not only the most successful, but also the most consistent team in J.League history. There have been three phases of particularly notable success – the first running from their initial league championship, in 1996, through to the Korea/Japan World Cup year in 2002; the second “golden era” was perhaps the most impressive, as the team won the league three times in-a-row, from 2007 to 2009; and the third phase began in late 2015, with a Nabisco Cup title, and continued with the stunning successes of last season.

But the Antlers organization never seems to lose its championship mentality. Even when the team is going through a “rebuilding phase” they remain formidable competitors, and often pop up as a cup finalist, or foil the hopes of a league rival with a key, unexpected victory. Considering this amazing record of success, you might think that Antlers have always been a fixture of football in Japan, but in reality, they are an “historical accident”, created out of thin air in a most unlikely location. In 1992, when the J.League was formed, no one could have foreseen that the team from Ibaraki would dominate the league’s first quarter-century of existence.

Kashima can trace their history back to the formation of the Sumitomo Metal Industries company team, in 1947, but until the start of the J.League era the team had caused no waves in Japanese football. Until 1974 they were little more than an informal club of Sumitomo Metal employees, taking part in inter-company competitions. In that year the company team entered the second division of the Japan Soccer League (JSL), and relocated its home field to Kashima, in Ibaraki Prefecture, which was home to one of Sumitomo Metal’s main factories. It was not until 1986 that the team managed to win promotion to the first division of the amateur JSL, and even after that, Sumitomo Metal Industries was a relative weakling compared to powerhouses such as Nissan Motors (later Yokohama Marinos), Furukawa Electric (the team that would bring forth JEF United) and Yomiuri Club (that would morph into Verdy Kawasaki).

The launching pad for Kashima’s rocketing rise to the pinnacle of Japanese football can be traced to 1991, when the leading members of the JSL decided to form a full professional football league, and the leading executives overseeing Sumitomo Metal’s football club decided to take a gamble on joining this new venture. The fateful event that laid the cornerstone for Antlers success was a meeting between some of these officials and the man who would one day be feted as “the God of Football” in Japan: Brazilian midfield sensation Arthur Antunes Coimbra, better known as “Zico”.

Kashima Antlers Logo:

|

|

|

Although Zico was already world-famous for his exploits at Flamengo, Udinese, and with the Brazil national team, his later career would become inextricably linked to the Antlers. In March 1991, the team approached Zico and asked if he would be interested in concluding his career at Kashima, and help launch the professional game in Japan. Zico was acclaimed as a superstar in his heyday, but by 1991 he was in his late 30s, and contemplating retirement. Kashima convinced Zico to join the team for its 1992 season - the final year of JSL play - to help it win a position in the soon-to-be-created J.League. The rest . . . as they say . . . is history.

At the start of 1992, the team changed its name to “Kashima Antlers”. The name is derived from the literal meaning of “Kashima”, which is “deer island”. The city is located on a sandy spit of land on the Pacific coast, at the mouth of the Arakawa River, and is surrounded on three sides by water. In the distant past the marshes behind this “island” were filled with wild deer, but today the only ones left in the neighbourhood are a few tame animals that roam the grounds of Kashima Jinja – one of the oldest and largest Shinto shrines in eastern Japan. To make their new“star player”feel comfortable, the Antlers adopted a colour scheme for their uniforms, emblems and flags based on the deep scarlet and black of Flamengo.

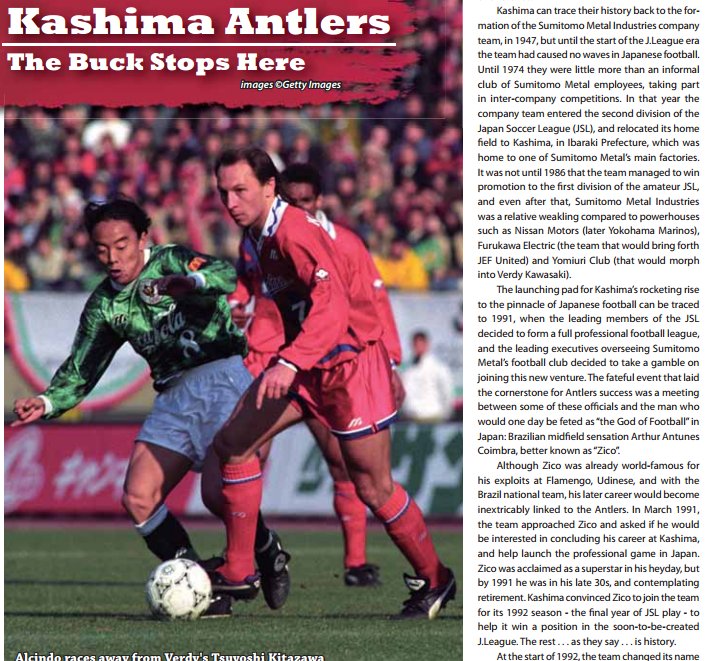

Led by Zico, and his Brazilian teammates Alcindo Sartori and Carlos Alberto dos Santos, Antlers finished high in the JSL rankings in 1992. But the greatest surprise was yet to come. In the very first stage of J.League competition, Kashima bested the league powerhouses, Marinos, Verdy and others, to secure the first-ever “Stage Title” trophy. In the 2nd stage they slipped to fourth place, as the JSL’s most decorated club, Verdy Kawasaki, claimed the stage title, setting up the first Championship Series, to be played between a well-known team of established stars from the suburbs of Tokyo - supported by tens of thousands of fans - and rank underdogs from a scruffy industrial backwater, with a tiny home stadium that seated just 15,000 (Kashima Stadium received a thorough renovation in 2000, expanding the end zones and adding a second tier to increase capacity and prepare it for the World Cup. The improved 38,000-seater opened in May 2001, and remains one of the largest football-only facilities in the country).

Despite the odds, and the fact that Verdy won their home leg comfortably (2-0), Antlers were doing their best imitation of David versus Goliath in the return leg. Alcindo scored an early goal and the Kashima players poured forward, pressing for the equalizer that would level the series. But on a rare counterattack, a Verdy player raced into the Antlers’ box chasing a long ball, and when he came shoulder to shoulder with a defender, flopped theatrically to the turf.

The 41-year-old Zico remonstrated with the referee as he pointed to the penalty spot, and when he was waved away for a final time, he walked past the ball that Kazuyoshi (Kazu) Miura had placed on the spot, and unloaded a generous mouthful of spit.

This earned Zico a yellow card, but this theatrical display only increased the respect and gratitude felt by Antlers fans. The bond between Zico and Kashima Antlers was so strong that even after he retired, in 1994, the team prevailed upon him to accept the job of technical director. Under his guidance, and leveraging his influence, Antlers were able to attract some of the best Brazilian coaches in the game, including Joao Carlos, Ze Maria and Toninho Cerezo. Zico even filled the coaching spot himself for a spell, after Ze Maria was released, the Brazilian number 10 playing an instrumental role in building the league’s most successful franchise.

Although Antlers (and Japanese football in general) attracted some world-famous players in those early years, including World Cup stars like Jorginho and Leonardo as well as Zico himself, the Brazilian influence on J.League growth is widely misunderstood outside Japan. Many have the impression that the J.League – like China’s Super League seems to be doing, today – was built on the shoulders of famous, highly-paid stars who carried their teams to success. In reality, the history of those early years was almost the polar opposite of that narrative.

While there were quite a few world-famous players in Japan during that period, most were well past their prime, and the most influential (not only Zico, but Carlos Dunga at Jubilo Iwata, Ramon Diaz at Yokohama Marinos and Careca at Kashiwa Reysol) were on the verge of retirement. Their main contributions came from the instruction and “peer coaching” they provided, and the example they set for Japanese teammates. Nowadays, if you ask any Antlers player why the team has enjoyed so much success, they will invariably talk about the “Spirit of Zico” and the “winning attitude and mindset” that the club tries to instill in every player. By serving as an example, counseling teammates or fellow coaches, and expressing the mindset of a champion, Zico helped to cultivate a team spirit and philosophy that persists to this day.

Brazilians have certainly contributed a lot to the success of J.League teams on the pitch, but the most influential have been hard-working journeymen who spent the vast majority of their careers in Japan. Examples at Kashima include Carlos Alberto dos Santos, Bismarck Barreto Faria and Fernando Almeida Oliveira. These “blue collar” players have always been more important to the success of J.League teams than the sort of “superstars” who jet in for a year or two, earn lots of money, and jet out for another destination in a year or two. In fact, recent experience (for example, Dwight Yorke, Freddie Ljungberg, Diego Forlan) suggests that the big stars tend to be more of a distraction than a benefit, disrupting team unity while not really making much of an impact on the pitch.

As important as the Brazilian contribution may have been in the early years, Antlers’ history of success also owes a great deal to wise management. From a very early stage, the whole Antlers organisation adopted a basic philosophy that remains to this day. From the outset, Antlers have retained a consistent team concept, based on ball possession and control of the midfield, solid defending, and quick interchanges on the wings. Not only has the team retained this basic philosophy for 25 years, but their personnel selections – not only players, but coaches as well – have been based on the team philosophy, and not vice-versa. Players and coaches come and go, but the basic Antlers concept remains the same.

If there is one individual who contributed more to that consistent record of success than any other, it is probably the fifty-something management wonk whose name is a near mystery to the general public (though every J.League “insider” regards him as an icon of the club). Mitsuru Suzuki took over as the team’s kyoka bucho (Personnel Manager) in the 1990s and has held the position for two decades. His job, essentially, is to scout, vet, background-check and sign every player or coach who joins the Antlers organization. Suzuki has benefited a lot from the quality of his direct superiors, including team presidents such as Hiroshi Ushijima - who was tapped to run Japan’s end of the 2002 World Cup - and Masaru Suzuki and Kazumi Oohigashi, who would both go on to serve as J.League Chairman. However, these officials were mainly in charge of the financial side of the business, whereas Suzuki is almost solely responsible for personnel decisions. He is the one whose keen eye for talent and connections to other football clubs worldwide have ensured the steady in flow of talent to the Antlers organization.

Although the positional qualities that Mr. Suzuki selects for derive from the “old-school Brazilian 4-4-2” style played by Zico and former Antlers coaches like Ze Maria, Joao Carlos and Toninho Cerezo, there are some other qualities or features that are consistently present in new Kashima acquisitions. Looking at the list of players that Antlers have signed over the course of the past two decades, it is very clear that the team values character qualities over sheer technical skill. The team does have a fairly good youth system, also, of course. On the current squad, for example, attackers Yuma Suzuki and Shoma Doi as well as the highly-touted U-20 defender Koki Machida are all products of the Antlers youth program.

However, compared to most other teams, Antlers have historically acquired a large percentage of their players from the university ranks. This might seem counter-intuitive, since players who turn professional straight out of high school are likely to spend a lot more time perfecting their ball skills and playing style. Yet the list of players who joined Kashima as 22 or 23-year old university graduates reads like an all-star team roster: Yutaka Akita, Naoki Soma, Yoshiyuki Hasegawa, Daiki Iwamasa, Yuzo Tashiro, Masahiko Inoha, Masaki Fukai and many more Antlers rookies did not start playing as professionals until after college graduation, and many more former university graduates have been acquired from other teams. Even among players who join the J.League from high school, the Antlers tend to select those who show above-average“intelligence” in their decision-making and tactical awareness. This is no accident, On the contrary, it seems a direct result of the hard work done by Mr. Suzuki and his scouting team, who appear to be far more selective when signing youngsters than many other J1 clubs.

One tribute to the strength of the Kashima scouting organization is the large number of former Antlers players who have left the club to become influential starters at other teams. Naturally, even for players who will eventually become stars, it is not always easy to break into a starting line-up in your first year or two. The Antlers have a long history of actively seeking good “learning opportunities” for young squad players. If they fail to find a starting position right away, they are usually loaned out to other league clubs at the first opportunity. Similarly, older players are often encouraged to leave the club as soon as their sharpness starts to decline, rather than them lingering at the club and sitting on the bench. As a result, several former Antlers went on to become “marquee” players at other clubs, including Jun Uchida (an icon at Albirex Niigata), Kenji Haneda (Cerezo Osaka) Masaki Chugo (JEF United and later Tokyo Verdy) and Tatsuya Ishikawa, who many in Yamagata regard as “Mr. Montedio”. Many others have returned to Kashima after their sojourns with other teams and become major contributors, such as Takayuki Suzuki and Takuya Nozawa.

The team that has benefitted most from this arrangement has been Kashima’s northern neighbor on the Pacific coast, Vegalta Sendai. Over the years, not only has Vegalta picked up core personnel from the Antlers bench, like Yuki Nakashima and Koji Kumagai, but an even larger number of Kashima players have moved to Vegalta for the final three to five years of their career, like Tomoyuki Hirase and Atsushi Yanagisawa, for example. Some might wonder how this arrangement benefits Kashima. After all, many players who are loaned out will develop ties to their new club, and move there permanently as soon as their contracts with Kashima expire.

Well, many of the players listed above did exactly that, and Kashima received little or nothing in return. Antlers also have a history of allowing young stars to accept offers from clubs in Europe, even in cases where the payoff is low. In the most well-known case, Olympique Marseilles used a loophole to stiff Kashima on a transfer fee for Koji Nakata, when they signed him in 2004. Nakata – a star at the 2002 World Cup – was valued at over 1.5 million euros at the time, and most legal experts thought that Nakata’s contract to Kashima was still in force. But the Antlers chose to let him move to Europe and get on with his career, rather than trying to block the move with a legal challenge. More recently, players like Yuya Osako (Koln), Atsuto Uchida (Schalke), Caio (Al-Ain) and Gaku Shibasaki (to Spain’s Tenerife) have been allowed to negotiate moves with little interference from the Antlers organization.

But by putting the careers of each player ahead of their own short-term interests, the Antlers reap plentiful long-term benefits. This can be seen with one glance at the current Kashima coaching staff. Nearly all of the current coaches and assistant coaches are former players, while others have graduated into coaching or management spots at other clubs in the league. And regardless of where they end up, most former players leave Kashima with fond feelings. No doubt Mr. Suzuki can depend upon his vast network of former players to let him know about a promising youngster who has not yet reached the radar screens of other teams’ scouts.

The continuing influx of top players has kept Kashima in the upper echelon of Japanese football since 1996, when they captured their first league title. They reclaimed the league trophy in 1998 and then embarked on their initial phase of glory. Over the next five years they captured three league crowns, four Nabisco Cups and two Emperor’s Cups, including the climactic 2000 season when they secured all three jewels in the J.League triple crown. During that period, the team also provided a large segment of the Japan National Team. Defenders Yutaka Akita, Naoki Soma and Akira Narahashi started for Japan at the 1998 World Cup in France, while midfielders Yasuto Honda and Chikashi Masuda both contributed to the team during the AFC qualification phase. The attacking partnership of Atsushi Yanagisawa and Takayuki Suzuki would feature heavily in Philippe Troussier’s Japan squad between 1999 and 2002.

However, after their Nabisco Cup triumph in 2002, Antlers entered a rebuilding phase as most of the old guard were replaced by younger prospects. The team already had a core of hungry young star- lets who had burst onto the national scene as members of the 1999 U-20 team which finished second at the FIFA Youth World Cup (as the U-20 tournament was then called). Aforementioned defensive back Nakata, midfielders Mitsuo Ogasawara and Masashi Motoyama, and goalkeeper Hitoshi Sogahata were all members of that squad, as was Tatsuya Ishikawa, a university student who would join Kashima two years later. Rather than ease the youngsters into the line-up gradually, while the veterans kept the team competitive, the Antlers opted to push through an immediate change of generations. Veterans like Akita, Soma, Narahashi and Koji Kumagai were traded to other clubs and the reins were handed to a group of fresh-faced kids. For five years, there were no additions to the trophy room underneath Kashima Stadium.

At the end of 2005, Toninho Cerezo stepped down after five years as head coach, and the team reached its lowest point under the brief and confused reign of coach Paulo Autori. But Kashima’s underlying success has always been founded on teamwork, a consistent game plan, and a consistent mindset that rarely changed no matter who was in the starting lineup. In 2007, Oswaldo Oliveira took over as the head coach and the young squad finally began to coalesce into a competitive unit.

In June, the management (probably led by Mr. Suzuki) concluded that the team was on the verge of another era of success, and lacked only an inspirational on-field general to put them back in the hunt for silverware. Mitsuo Ogasawara had departed for Europe the previous year, accepting an offer from Italy’s Messina, but despite a few good outings he was not settling in as a regular player, so when the Antlers organisation asked him to come back and anchor the midfield, he accepted. Antlers’ subsequent winning streak - which would eventually stretch to 14 games - launched them on a dramatic late run, making up ten points in the final five weeks to overtake Urawa Reds and win the championship on the last day of the season.

While Ogasawara captured the hearts of Antlers fans with his “prodigal son” return and inspirational play, the Antlers were already nurturing a new generation of stars. Motoyama, Yanagisawa and Sogahata, along with Nozawa and Takeshi Aoki were veterans of the first “Golden Era”, but a new crop of young bucks were now making key contributions to the effort. In 2008, this younger generation started to come into their own. Defenders Uchida and Iwamasa provided defensive solidity that recalled the days of Akita, Soma and Narahashi, while Shinzo Koroki took over the central striker role as Yanagisawa’s partner. The team had also picked up some useful mid-career players from other teams, who would establish themselves as Kashima favourites over the next few years - in particular, wingback Toru Araiba (from Gamba Osaka) and defensive utility-man Masahiko Inoha (from FC Tokyo). Together with Brazilians Marquinhos and Danilo, the Antlers marched smartly through the 2008 season to their sixth league title, and followed up this success with a third consecutive league title in 2009, confirming their status as the J.League’s most successful team ever.

The 2009 season marked the high-water mark of Kashima’s second golden period. As the J.League moved into an era of greater parity, Antlers had increasing diffculty maintaining the dominant posi- tion they had held during most of the J.League’s first two decades. However, their resilience as a club, and the winning mindset that was instilled into every player allowed the team to remain consistently among the front-runners. The fine coaching of Oswaldo Oliveira, a former World Club Championship winner with Corinthians, was important in cultivating this new base of players. Antlers claimed their 14th major title on New Year’s Day 2011, with a victory in the Emperor’s Cup, kicking off a 2011 campaign that would be coach Oliveira’s last. He stepped down in December of that year after what surely ranks as one of the most successful coaching careers in J.League history. He led the team to three consecutive league titles, and secured all of the major domestic trophies (J1, Emperor’s Cup, Nabisco Cup and Xerox Cup).

As the Oliveira era drew to a close, Kashima’s core was aging once more, and it was already clear that the baton would need to be passed to a younger group of players. In 2012, former Antlers player - and Brazilian World Cup star - Jorginho took the reins of the club as head coach, and began the process of moving older veterans out of the way to make room for promising young players, allowing them to blossom into solid contributors. Uchida and Inoha had already departed, for Europe, and during the 2012 off-season, Nozawa and Tashiro moved to Vissel Kobe, leaving only Ogasawara, Motoyama and Nakata from the squad that won the treble in 2000. Many wondered if the team would be able to rebound as quickly as they did at the end of the 90s.

This concern was far from empty. Indeed, Kashima spent the next few years struggling to overcome the inexperience of its many first-, second- and third-year players, all of whom were asked to play key roles. Jorginho lasted only one season, and was replaced after setting a team record for the lowest finish ever (11th place). Nevertheless, he did his job quite well, clearing the decks of vet- erans and handing the torch to a new generation. In 2013 and 2014, Toninho Cerezo was invited back for his second stint as Antlers head coach. He helped the team complete its generational shift, and laid a solid foundation for the future, as well as adding to the trophy cabinet with a Nabisco Cup title in 2013.

In 2014, however, management decided it was time to signal a completely new era, and handed the coaching reins to former Antlers defender Masatada Ishii, who had taken part in the team’s very first league championship season in 1996 (see our classic vintage pictures!). This was the first time since 1998 that a non-Brazilian had held the job, and Ishii would become the first Japanese coach to lead the Antlers to a league title. The decision proved to be very timely, as Ishii’s slightly more conservative philosophy was key to a victory over Gamba Osaka in the 2015 Nabisco Cup.

The 2016 campaign would confirm Kashima’s emergence into a third era of success. The competi- tive landscape in Japan has changed greatly over the past 25 years, and it is hard to imagine any team - even the Golden Herd of Ibaraki - achieving the sort of dominance that they enjoyed at the turn of the century, or even in the Oliveira years. Not only has the pool of talent been divided more broadly - among 54 teams and counting - but the influx of money from the J.League’s new media deal with DAZN should allow all J1 competitors (and below) to strengthen their squads. The top J1 teams also now face a very diffcult balancing act, as Asian Champions League commitments conflict with efforts to secure domestic silverware. Nevertheless, with three titles in the past two years (one from each major tournament), Antlers have proven themselves to be a consistent title candidate.

The current squad is stocked with talent, and many of the most exciting prospects are still on the upward slope of their careers. Although Gaku Shibasaki’s starring role at the 2016 Club World Cup earned him his move to Spain, established players like Daigo Nishi, Yasushi Endo, Mu Kanazaki and Atsutaka Nakamura are still around, and reaching their prime, while youngsters like Gen Shoji, Naomichi Ueda, Doi and Suzuki are beginning to settle in as first-team regulars.

The most critical question for Antlers this season is whether they can keep their younger stars in the herd, or if they will make the jump to Europe (or as Caio did in mid-2016, to the Middle East). The team signed two proven (and “Japan- settled”) Brazilians over the winter break – Leo Silva from Albirex Niigata and Pedro Junior from Vissel Kobe – as well as two very promising youngsters, in Avispa Fukuoka’s Takeshi Kanemori and Shonan Bellmare’s Yuto Misao. So far the only departure of real note is Shibasaki.

Regardless of who stays and who leaves, the team never seems to lose the champion-like mentality that Zico planted in the rich soil of Ibaraki, way back in 1992. Somehow, the “Spirit of Zico” always seems to sprout anew in the subsequent generation. Whatever happens, you can be sure that the team, the club, will make its presence felt. The competitive balance in the J.League may change from year to year, but it is always a good bet that Kashima Antlers will be in the thick of the chase.

Copyrights to all text and descriptions belong to Ken Matsushima and J.Soccer.com. All images are property of J.League Pictures, and supplied for the exclusive use of J.Soccer.com

Hits: 6863

Sumitomo Metals FC Logo

Sumitomo Metals FC Logo